Diving back into old National Geographics, I recently surfaced with a few treasures:

There is a story in this caption on page 583 in the May, 1914 issue of National Geographic, the photo by Shirley C. Helse, showing a very beautiful young woman in a white dress sitting on a chair. The woman, here referred to as a “girl,” is given no name. Some might write this story as a romance, but I see elements of alcoholism, addiction, exploitation and possibly rape. My sympathies are, of course, with the woman, but I would write her as strong and canny, seeing a rare opportunity and taking as much advantage of it as she could.

This Mexican girl was for several years nurse and doctor's assistant at Boquilla. She attracted the doctor's attention by her interest in the affairs of the hospital and from an ignorant untrained beginning she came in time to take full charge of the doctor's work during his illness or absence. She has upon occasion successfully performed surgical operations, herself giving the anesthetic with no help but that of a mozo [male household servant].

Reading further, the June issue of 1914, just two months before the guns of August, carries a hopeful message to the graduating class of the Friends’ School in Washington, D.C., from Alexander Graham Bell. Bell and Thomas Edison were the Steve Jobs and Bill Gates of their day, and I can just imagine the nerds of 1914 thinking that nothing but blue skies were, literally, in their future.

It was only a short time ago that if you wished to express the idea that anything was utterly impossible you would say, “I could no more do that than I could fly.” …

[Today] It is only a few years since the first man flew, and we are only at the beginning of aviation. What a delightful idea it is to go sailing through the air. The only trouble is that you must come down, and we have altogether too many fatalities connected with the work. Here, then, is a subject for you to explore: How to improve the safety of the flying machine. How to produce flying machines that any one can fly. …

… A man proposes to try this summer to fly across the Atlantic Ocean in a heavier-than-air flying machine. The strange thing about the matter is that experts who have examined into the possibilities find that he really has a fighting chance…

Calculation shows that … our best machines should be able to cross the Atlantic in 13 hours. I hardly dare to say it aloud for publication. It is sufficiently startling to know that it is not only possible, but probably, that the passage may be made in a single day. [P255]

Bell was ahead of his time. The war was about to suck all of the oxygen out of the fathers and mothers of invention. Charles Lindbergh didn’t cross the Atlantic until 1927, and it took him more than one day. I wonder how many boys of the graduating class of 1914 survived to celebrate it.

And then there is this gem. The final piece in the June, 1914 issue of The National Geographic Magazine carries an account of a banquet at which Colonel George Washington Goethals is awarded a gold medal from the National Geographic Society for his work in completing the Panama Canal. The luminaries are, well, luminary. Gilbert H. Grosvenor, in his introductory remarks, proudly notes that,

There is not a community of one hundred white people in the United States where a member of our Society cannot be found.

He then introduces the Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan, who in turn introduces President Woodrow Wilson, who had an interesting (and I think currently timely) observation of his own:

I am glad that this thing was not done by private enterprise, and that there is no thought of private profit anywhere in it, but that a government put itself at the service of the world and used a great man to do a great thing. That is the ideal of the modern world, that the services to mankind shall be commonly shared.

Two other speakers rose to make salutary remarks, not only about Col. Goethals but also about each others' countries: the French and German ambassadors. If there is any awareness of the horror to come in a few months' time, there is no hint of it here.

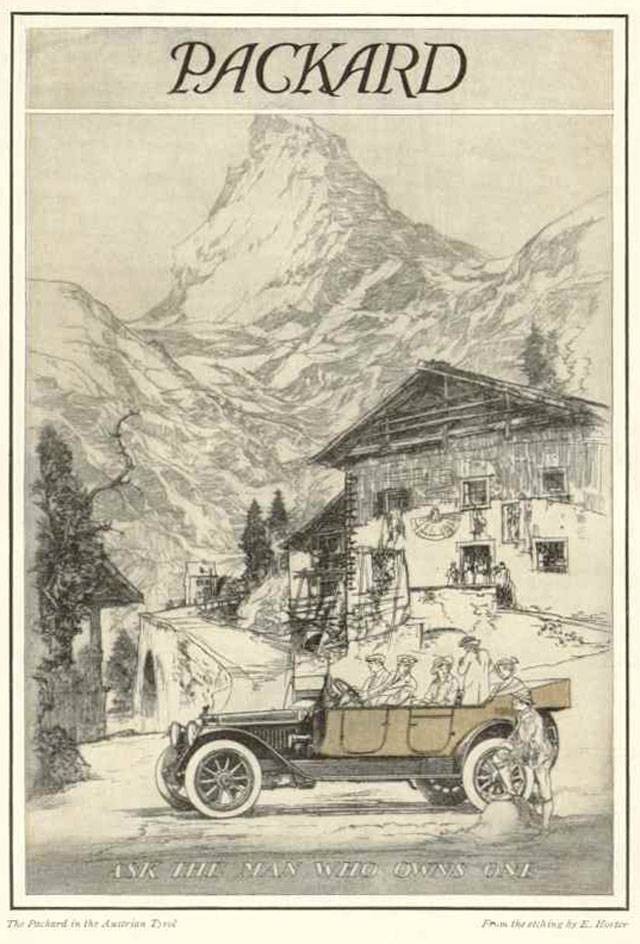

I always glance through the ads at the end of the issues. This month included ads for Campbell Tomato Soup, Victrola, and Kodak. My favorite, however, is the ad for the Packard, given pride of place on the back cover, an etching by one E. Horter imagining a group of happy people enjoying themselves in the Austrian Tyrol. In their Packard.